Great Feeling Wants a Container: Thoughts on Space and Home

by Claudia Ware

“My house is diaphanous...its walls contract and expand as I desire. At times I draw them close about me like protective armour. But at others, I let the walls of my house blossom out in their own space, which is infinitely extensible.”

— Georges Spyridaki, Lucid Death (1953)

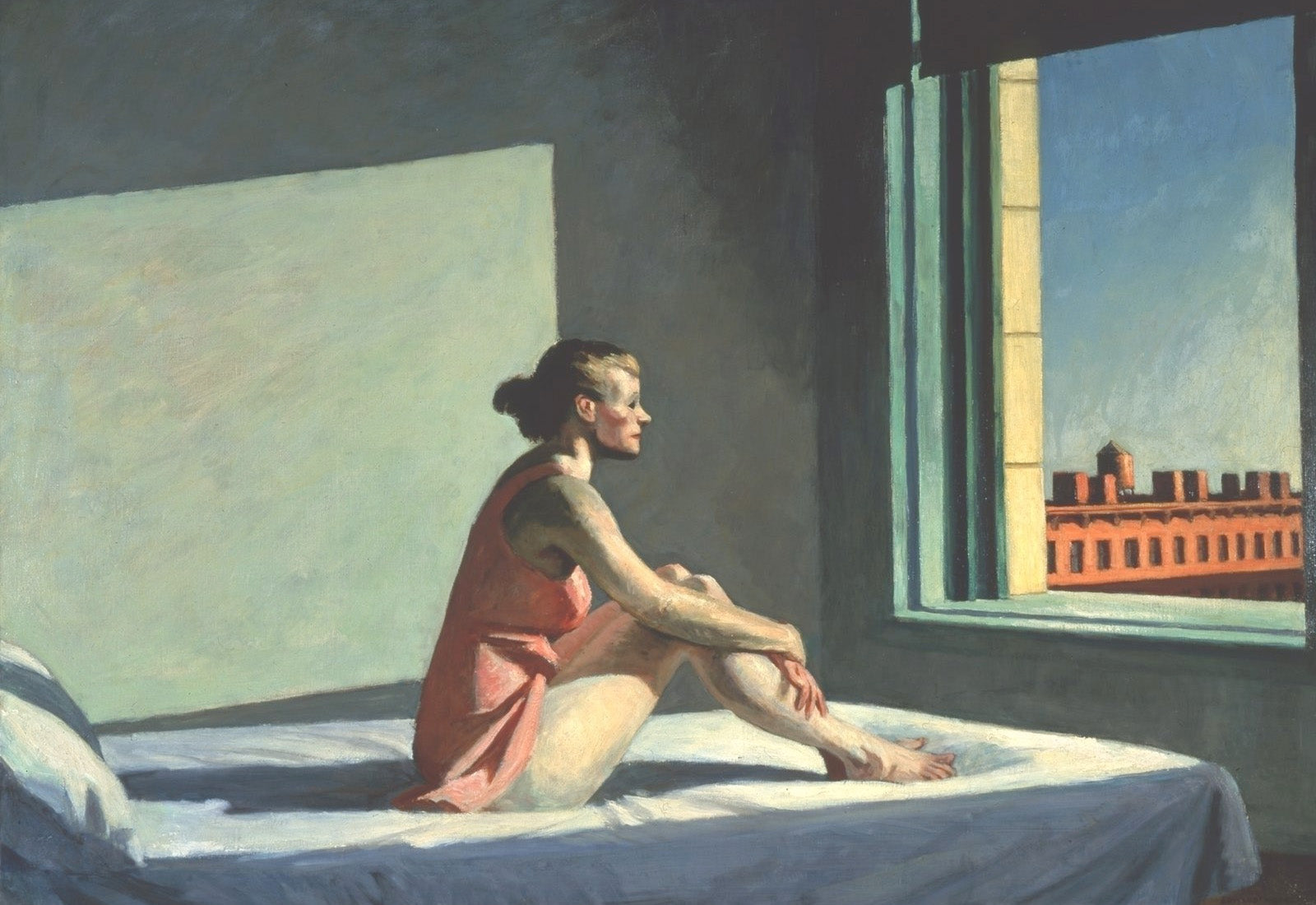

Morning Sun, 1952, by Edward Hopper (oil paint)

On the day P left her marriage, we bolted from the theatre and walked down Boundary Street in search of a divorce-kebab. It was a fitting way to end the day. Us — exhausted, blissed out on the heavy warmth of a greasy meal. P — grief-ridden, me — along for the ride. By some stroke of luck, we’d found ourselves working on the same project at the state theatre company up north, old friends-cum-colleagues. By greater luck, and perhaps providence, we found ourselves living on the same street. For nearly three months, we relished the domesticity of daily friendship, the intimacy of tracking with someone day in day out, of having nothing to catch up on and therefore everything to say. It was a Monday when we ordered our divorce- kebabs; an early curtain call, an earlier-than-usual bedtime. The sky stretched bruised blue above our heads, autumn wind tickling with the edges of winter. I snapped a photo of P on my phone — the night you left your husband, I said, one for the grandkids. In the photo, P clutches her divorce-kebab with two hands as if it might escape. She is all gums and teeth, eyes sloped in smile, wide and terrified.

The house, she said, reality leaning on her, where am I going to go? I need to leave that house.

As the season rolled on, P and I fascinated ourselves with houses. In the dim blue of the wings, we whispered our tenancy dreams until the cue-light blinked orange, then green — go. P searched for a three- bedder sanctuary, I looked for a studio, a room of [my] own.

*

I recently read a poem by Jeffery Skinner, which included the lines:

Quatrains are useful because, as Creeley said: Strong feeling wants a container.

I was taken by this and sent it to my poet-friend, B. He never responded, so I imagine he did not see what I saw or feel what I felt. Just as a quatrain might form a stanza, a stanza forms a room — a container. After all, that’s what ‘stanza’ means — room, chamber, lodging, or stopping place. A room for the poetic, a chamber for feeling, a container for imagination.

*

P and I had the same move-in date for our respective stanzas. June 26th. While I packed boxes, she divided assets, fighting for pieces of a house that were home to her — a grandfather’s desk, a family heirloom, a father’s parting gift. The spare room in my parent’s house was explosive with my own ‘assets’, things I’d collected over the years and, for some reason or other, hung on to.

One morning P sent me a poem she’d written with the lines:

The division of assetsTells me what parts of my soul

Things — I often think this — are never just things. They are the grout of home, sites of memory, aspiration, and personhood. A thing is a clamorous husk.

Even when one is no longer attached to things, it’s still something to have been attached to them; because it was always for reasons which other people didn’t grasp.

— Proust, Cities of the Plain

*

The day I moved into my apartment, I sat on the cold timber floorboards surrounded by my things; boxes of books, my piano — Florence, our family’s old music cabinet, my great-grandmother Alice’s Victorian- era hatbox, the chair I reupholstered with my mother, a family portrait from the ’90s, an artwork by my ex’s-ex. It wouldn’t have felt right, moving to a new place without these things to cover the walls and floors and shelves. Besides, you cannot shed the skin of the past by moving to a new home [oh lordy, I’ve tried this], if anything, you only dangle it further behind you, having loosened its purchase on your soul.

There was one box I was reluctant to unpack. It sat on the passenger seat of my car for a fortnight, tightly bound, winking. The box contained memorabilia from my early 20’s — a time of great pain, confusion and embarrassment. A time dominated by the colour blue. I didn’t want to see Her, the woman contained in the box. I did not resonate with Her anymore, or, at least, I didn’t want to. Most of all, I had no desire to re-live her pain.

The work of memory collapses time.

— Walter Benjamin

When I did open Her box, I was surprised by the sheer volume of letters and cards — mostly from my immediate family. Handwritten notes were a significant trope of my upbringing. On special occasions, the emphasis was always on the note, not the gift. The phrase cards are personal was [and still is] delivered accusingly to anyone who dare read a note not addressed to them. Our cards were a written excavation of everything we felt and appreciated about the recipient. I had no notion that other families didn’t share our tradition until I left home and continued to write letters of this nature to friends who were surprised, and at times embarrassed, by my cards are personal tendencies.

The first letter I pulled from Her box was from my childhood best friend — do not read until approx. 20000 ft above the ground, the envelope said. I was eighteen, on my way to live in Western Australia. In her letter, she tells me she loves me and advises me to file [my] grotesque fingernails [I’ve never been one for nail care]. But the rest of Her box bore a weightier tone. I knew my father and I exchanged letters during my years in Perth, but I had forgotten just how many he sent.

Dear Claudette, they began.

Don’t be fooled into thinking the world isn’t wonderful — it is. You are.

My parents were grappling with the woman I’d become, attempting to reconcile themselves with the girl they’d raised and the cloud of blue that had taken her hostage.

I hope and pray that you become entirely yourself.

I didn’t know what ‘myself’ was, nor where to begin finding her.

In another of my father’s letters, he writes about seasons and suggests I listen to ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ by The Byrds.

To everything (turn, turn, turn)

There is a season (turn, turn, turn)

And a time to every purpose, under heaven

At the bottom of Her box, I found a letter written in child-like handwriting from my first attempt at a boyfriend [the one with ‘ChicksFootyBeer’ tattooed on his foot]. There was no date, but I sensed the letter was written the week I first tasted infidelity. The word ‘secrid’ appeared seven times.

It took a moment to unpick his misspelling.

Sacred.

Sounded about right.

There was very little he considered sacred.

Least of all my body.

Least of all my soul.

Though to be fair, I’m not sure I had a great sense of sacred myself. Looking back, fingers over eyes, I see a young woman utterly, despairingly lacking in self-possession.

Stay classy, my father signed off.

If only I did.

*

Soul. Is it too histrionic, too sticky and woo woo, to talk about ‘souls’ — whatever that may mean? The word makes me cringe, but as someone with an appetite for the sentimental, it is somewhat unavoidable. After all, isn’t it the soul that makes a person a person, not just a body? If the body houses the soul, then the soul cradles the person.

A few months ago, my brother and I drove out to say goodbye to our beautiful Nana, Gladys, aged 94. But as I held her hand, kissed her cheek and told her how much I loved her, I felt I was saying goodbye to the body, the house — the occupant had long since disappeared. Her embers had cooled.

A house then is also a kind of body. Just as our ‘soul’ clings to organs and bones and blood, we attach ourselves to walls, floors, and things. Like matryoshka dolls, the house contains the body, which contains the soul, which contains the person.

The house, even more than the landscape is a ‘psychic state.— Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (1958)

Bachelard’s work is a passionate exploration of homes and spaces and an invitation to think figuratively about these images. In one chapter, he recalls an exhibition organised by French-Jewish psychiatrist Francoise Minkowska, who studied drawings of houses done by children during WWII. She found that children who had not endured hardship during the war drew houses that were well-lit, proportional, and robust. For them, the house was a safe, sacred space. Conversely, Jewish children who had suffered during the German occupation drew “motionless houses” — they were cold, angular, and ill-proportioned, with sparse landscapes and sentinel-like trees guarding the building. For these children, the house was more secrid than sacred.

The Bachelardian house is, at its best, a site of immense intimacy.

The house [is a] study of the intimate values of inside space.

I am hospitable to this idea. It runs contrary to the macroness of contemporary life, the exteriority with which we broadcast our voices, thoughts, and identity through the World Wide Web. For Bachelard, it is in the privacy of the house that dreaming takes place:

The house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.

And what, then, is the virtue of daydreaming [if not simply for the sheer pleasure of idleness]? I might suggest that art — broadly speaking — offers us fodder for dreaming, and that daydreaming is the personalisation of that fodder. Daydreaming is the root of becoming, a means by which to consider the possibilities of oneself. To daydream is to acclimatise to one’s acoustics, to offer the wisdom of imagination to the rigour of knowledge.

Bachelard attributes maternalistic qualities to the home. Here, I am less hospitable. I understand what he’s getting at — the house is protective, sheltering, nurturing — qualities we most readily attribute to women, and in particular, mothers. But it smacks of Coventry Patmore’s ‘Angel of the House’. In her most recent ‘living autobiography’ Real Estate (2021) Deborah Levy offers a more gender-neutral way of thinking about the home:

Domestic space, if not societally inflicted on women, if it is not bestowed on us by patriarchy, can be a powerful space...In fact, is it domestic space, or just space for living?

Spaces for living — I’m on board with this.

*

Since leaving the family home at eighteen, I’ve lived in six different share houses with twenty-three different housemates. I grew up in a family of seven; we shared bedrooms, bathrooms, corridors — we shared spaces for living. I consider myself a hospitable person. I don’t always get it right, but I’m comfortable with co- existence and find it relatively easy to synchronise with other people’s rhythms — What do you need me to be? I’m flexible, a wad of clay, supple, malleable. How do you need me to be? People stain me the way turmeric turns the benchtop yellow. I’ve been a someone to somebody many times over — a daughter, a friend, a sister, a colleague, a teacher, a girlfriend, a housemate, a stranger-turned-housemate-turned-sister, a friend-turned- housemate-turned-stranger. Existing in relation to others, accommodating difference, is cosy and good. [I also wonder if it is slightly gendered — most woman I know are highly skilled at facilitating the moods, lifestyles, and experiences of others, often denying their own in the process.] But flexibility without personal clarity is self-betrayal. I’ve learnt this the hard way.

At twenty-seven, I decided to live on my own — bold, given my proclivity for co-existence. I knew there’d be times when I would feel the sting of loneliness and miss the familial atmosphere of the share house, but I was eager for the crystallisation living alone might offer: Who am I when no one is around? What are my tides, my cadences?

*

The day I moved into my one-bedder, Sydney went into lockdown. Trial by fire. I shuffled from room to room, rearranging my things, chasing patches of winter sun. I found my local coffee shop, they learnt my name, I played Florence, I lay in bed at dawn to watch the sky turn champagne, I waited for the thin lozenge of sun to claw through my south-east window at 7:35am before losing its grip, heading north, I watched the light drop low in the late afternoon, smashed peach spun with heavy blue. Most of all, I acclimatised to myself, and watched the space become an extension of me.

*

Lately, I’ve been good at watering my houseplants. I’m no green thumb, but my friend A gave me a monstera as a housewarming gift, and I’m desperate to keep her alive. I dust her broad green leaves and notice a new one, tightly furled within the stalk of another, all lime and supple, just waiting to uncurl her fingers, waiting patiently to stretch up toward the ceiling and grow into this space for living.

I call P from my one-bedroom stanza. Across the line, I hear J, her youngest daughter thumping books off the shelf while M, the elder, watches playschool. P has been writing poems [good ones] and is daydreaming about pink bed linen. We talk about pink, about what a good colour it is, about how she deserves divorce- linen in her new home. P thinks she is going to buy them, and I say yes.

*

Works Mentioned:

Bachelard, G. (1957). The Poetics of Space

Levy, D. (2021). Real Estate: A Living Autobiography.

McGahan, A. (2021) Collected Poems.

Proust, M. (1921). Cities of the Plain.

Skinner, J. S. (2020). The Cloud. In The Paris Review (Vol. 234).

Spyridaki, G. (1953). Mort lucide (French Edition).

1 comment

What a stunning homage to the complex and visceral concept of home! It resonates deeply for me in a year where I moved to a new house and felt miserable and lost before transforming it into a new, braver and beautiful extension of myself. Now I never want to leave.

Laure

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.